- Introduction

- Overview

- Basic Concepts

- Versioning

- rez-config

- Packages

- rez-env

- Patching

- Piping and rez-run

- Failed Resolves

- Package Variants

- rez-build

- Timestamping

- Anti-Packages and the Conflict Operator

- Weak Package References

- rez-release

- Bundles

- Wrappers

- Exposing Third-Party Software to Rez

- More Tools

- Conventions

- Troubleshooting

- Common Pitfalls

- System Environment Variables

- Further Work

Introduction

What Is Rez?

Rez is a suite of tools for resolving a list of ‘packages’ (versioned software) and their dependencies, into an environment that does not contain any version clashes. Rez also includes a cmake-based build system, which is integrated into the package resolution system, and a deployment system, for publishing new packages.

What Is Rez Not?

Rez is not a production environment management system, it is a package configuration system. To illustrate the difference, consider:

“Package configuration” answers the question, “if I want this set of packages to function within a single environment, what set of packages, environment variables etc do I actually need?”

Whereas “Environment management” answers the question, “What set of packages do I need in this area of production, and how do I manage adding new packages, and updating versions?”

Whilst Rez is not an environment management system, it would make sense to build such a system on top of Rez, and that’s exactly what was done internally at Dr D studios. The environment management system determines what packages are needed where, then this package request is given to the underlying Rez system, which resolves the request into a working environment.

This decoupling allows the user who does not need to be working in a production environment (eg, someone developing core tools) to use only those packages they need. It also guarantees that only valid, non-clashing environments are ever generated.

Overview

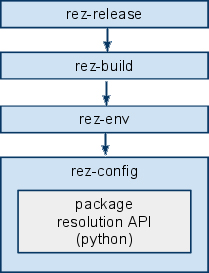

The ‘package resolution algorithm’ is the main component of Rez and is written in python, with supporting tools written in python and bash. It has cmake integration, and comes with a set of cmake modules for building common types of targets, such as python scripts. The python component is written as an API, so we can programmatically manage environment configuration in future.

There are four major tools that make up the system, and a smattering of support tools. They can be thought of as a stack, where the tools at the bottom underpin those at the top:

This manual will start with the basic concepts of the system, and will illustrate its use in a run-time context. Later chapters will introduce the build system support, and more advanced topics. Tools will be introduced from the bottom of the stack upwards - it is necessary to understand the underpinning tools first, before their dependent tools can be described.

Basic Concepts

Rez manages packages. You request a list of packages from rez-config, and it resolves this request, if possible. If the resolution is not possible, the system can supply you with the relevant information to determine why this is so. You typically want to resolve a list of packages because you want to create an environment in which you can use them in combination, without conflicts occurring. A conflict occurs when there is a request for two or more different versions of the same package - a version clash.

Rez lets you describe the environment you want in a natural way. For example, you can say:

“I want an environment with...”

- “...the latest version of houdini”

- “...maya-2009.1”

- “...the latest rv and the latest maya and houdini-11.something”

- “...rv-3.something or greater”

- “...the latest houdini which works with boost-1.37.0”

- “...PyQt-2.2 or greater, but less than PyQt-4.5.3”

A package is a particular version of a piece of software, or possibly data or configuration information, that resides in a single physical location on disk. The rez system does not distinguish between external and internal software. Some examples of packages include:

- boost-1.33.1

- houdini-11.0.438

- foo-2.9.0

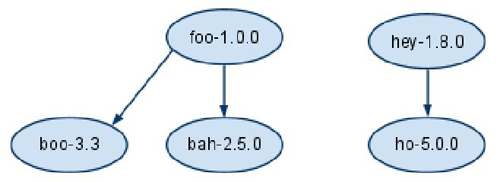

Packages have dependencies, ie other packages that they need in order to function. When you request a list of packages from rez, it analyses the dependencies of all the packages in the request, and returns you a resolved list of all the packages you actually need. For example, consider the following:

In this example, there are five packages on disk (for the moment we don’t care where they actually reside on the file system). Let the arrows in the diagram, and in all diagrams from here on, denote dependencies - for example, package hey-1.8.0 requires package ho-5.0.0.

Let’s say that we want to make a request for the packages foo-1.0.0 and hey-1.8.0. The result would be:

request: foo-1.0.0, hey-1.8.0

response: foo-1.0.0, hey-1.8.0, boo-3.3, bah-2.5.0, ho-5.0.0

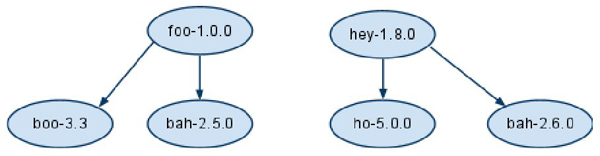

Let’s take a slightly different example:

Here the result of a rez-config request would be:

request: foo-1.0.0, hey-1.8.0

response: Not possible: conflict (bah-2.5.0 <--!--> bah-2.6.0)

In this case, the request was not resolvable, because foo and hey need different versions of the same package (bah). Rez does not allow this (“but what about static libraries!” I hear the C++ programmers cry. We’ll get to that later, in build-time dependencies).

Packages describe their dependencies in a metafile which is installed as part of the package itself. When rez-config is run, it finds the packages in the request, and reads each package’s metafile, in order to find and resolve further packages. The system is completely decentralised, there is no central store of information - all information relevant to a given package is installed with that package.

These examples are simple, but they illustrate a key concept - rez-config can take a list of packages that you request, and resolve it into a full list, including dependencies, which have been verified for compatibility. You do not need to have knowledge of those dependencies, or of possible conflicts - the system will not allow an invalid configuration to be generated.

Versioning

Before an in-depth discussion of the Rez tools, we need to describe how the system deals with version numbers. Packages in the Rez system are versioned using the format:

[a-z | (1-9)(0-9)*](.(a-z | (1-9)(0-9)*))* (for the regular expression geeks)

In other words, the following are examples of valid package versioning:

- foo

- foo-1

- foo-1.2

- foo-1.2.3

- foo-1.2.3.800.7

- foo-1.2.3.a

- foo-1.b.1

When requesting packages in Rez, you do not need to ask for a specific version of a package - you can instead ask for an inexact version. For example, let’s assume that the single package foo-5.6.1 exists on disk, and there are no other foo packages. The following package descriptions will all resolve to foo-5.6.1:

| Package Request | Meaning |

|---|---|

| foo | any version of foo |

| foo-5 | foo-5, or foo-5.X(.X.X.X...) |

| foo-5.6 | foo-5.6, or foo-5.X(.X.X.X...) |

| foo-5.6.1 | exact match |

| foo-5+ | foo-5(.X.X...) or greater |

| foo-5+<5.7 | foo-5(.X.X...) or greater, but less than foo-5.7 |

| foo-0+<4.5 | any foo version less than foo-4.5 |

It is also possible to describe disparate regions in an inexact version, although in practice it would be rare to use this description directly (it exists because it is used internally by the resolution algorithm):

foo-5.6|6.3 (“foo- 5.6 OR 6.3”)

foo-3|5+ (“foo- 3 OR (5 or greater) ”)

rez-config

rez-config is the largest and most important tool in the suite. It contains the algorithm which resolves packages into a valid package configuration (details of this algorithm are beyond the scope of this document).

rez-config understands version numbers as mathematical entities. It does not treat them simply as tokens. If you ask for “boost-1” then it understands that this could match “boost-1.33.1”, “boost-1.37.0” etc. Internally, it is able to perform set-like operations on them, such as unions and intersections, and this is utilised by the resolution algorithm.

The rez-config tool prints information, it does not do anything interactive or alter anything anywhere. Dependent tools such as rez-env take information from rez-config and actually do something with it.

So let’s start with some usage cases. Let’s say we want an environment with a specific version of houdini in it:

> rez-config houdini-11.0.438

successful configuration found after 0 failed attempts.

Not very exiting, and what’s this “failed attempts” all about? More on this later. rez-config has done something here, but you haven’t specified what information you want. Let’s try again:

> rez-config --print-packages houdini-11.0.438

successful configuration found after 0 failed attempts.

python-2.5

boost-1.37.0

houdini-11.0.438

lin64

So here rez-config is showing you the list of packages that an environment configured for “houdini-11.0.438” will actually contain. So let’s say we want the latest version of houdini, rather than a specific version:

> rez-config --print-packages houdini

successful configuration found after 0 failed attempts.

python-2.5

boost-1.37.0

houdini-11.0.477

lin64

So we’ve gotten 11.0.477 and at the time of writing, this is the latest houdini version available. But wait - doesn’t “houdini” match to “any version of houdini,” according to the last chapter? Why did we get the latest version? the answer is in a default rez-config flag ‘--mode’, which is missing from our example:

> rez-config --mode=latest --print-packages houdini

successful configuration found after 0 failed attempts.

python-2.5

boost-1.37.0

houdini-11.0.477

lin64

So here the output is the same. Available modes are earliest, latest and none. ‘None’ exists only for debugging purposes, and ‘earliest’ I expect to be rarely used. When rez-config is confronted with an inexact package which it can resolve no further, it will then go to the file system in order to resolve it, and it’s this ‘mode’ flag which determines how the search is done.

You can use any kind of inexact versioning to describe the packages that you want. Bear in mind you may have to escape with single quotes (‘’) due to bash. Here’s an example where I want an environment with the latest version of delight, but less than 9.1:

> rez-config --print-packages 'delight-0+<9.1'

successful configuration found after 0 failed attempts.

delight-9.0.58

lin64

Isn’t this fun. Let’s try something more interesting, and ask for an environment with more than one package. So note than in our request for ‘latest houdini’, one of the resolved packages was boost-1.37.0, and the version of houdini resolved was 11.0.477. What will happen if we request houdini in combination with a different version of boost? We might expect it to fail, let’s see:

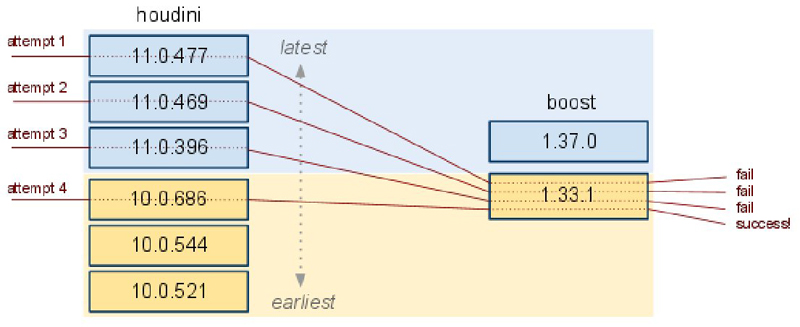

> rez-config --print-packages houdini boost-1.33.1

successful configuration found after 3 failed attempts.

python-2.5

boost-1.33.1

houdini-10.0.686

lin64

What the? The configuration did not fail... but notice that it’s returned us a different version of houdini, one that isn’t the latest. Notice also that there were three “failed attempts.” What’s going on?

rez-config, when run in ‘mode=latest’, will give you back the latest possible combination of packages that you asked for. This may not necessarily be the very latest version of every package. In this example, houdini-11.0.477 is not compatible with boost-1.33.1, so that combination was not chosen. This diagram illustrates the resolution process that took place:

Here, the stack of houdini versions illustrate the packages that rez-config found on disk. The houdini versions in blue require boost-1.37.0, and those in yellow require boost-1.33.1. Rez-config can’t know this ahead of time, so it starts with the latest version of houdini and attempts to resolve that configuration. If that fails, it moves down to the next latest version, and tries again1. It will do this until a match is found, or all versions of houdini are exhausted. You can see that in this case, it took three attempts before a valid configuration was found. If there are multiple inexact packages in a request, then rez-config will perform this kind of search recursively.

This a a trivial example where the conflict could have been spotted by eye. However, realistic configurations quickly get a lot more complicated, and often conflicts occur between packages due to secondary or tertiary dependencies, or dependencies even further removed.

When rez-config refuses to resolve a set of packages for you, it is often not immediately obvious what the problem is. However, rez-config has debugging features which enable you to get a clear picture of why that particular configuration is not possible. This is described in a later chapter. In the meantime you can use the --verbosity flag, although its output is daunting. For details of available flags, see rez-config’s command-line help (all Rez tools have help, accessed either with no args, or ‘-h’).

We’ll leave rez-config for now, and take a closer look at the things it manages: packages.

Packages

As described earlier, a package is a particular version of software, or a collection of data or configuration information, that resides in a single location on disk. Packages contain a metafile which describes, among other things, the packages that that package depends on.

Rez-config finds packages by searching in the paths listed in the REZ_PACKAGES_PATH colon-delimited environment variable. This variable, and a host of others, are setup by Rez’s initialisation script (init.sh), which is usually sourced from your .bashrc file, or equivalent startup script. The typical value of this variable is:

${HOME}/packages:/some-configured-location/packages

Ignore the user-specific path for now. Notice the second path. This is where most packages are installed to. The actual location is set when rez is configured and installed for the first time.

Let’s consider a theoretical package, foo-1.0.0, which contains just a data file and an executable binary. Foo’s directory structure would look something like this:

/rez/packages/foo

|-- 1.0.0

| |-- package.yaml

| |-- bin

| | `-- foo

| |-- data

| | `-- foo.data

The first directory, ‘foo’ is the package family directory. This directory contains subdirectories which are package versions - in this example, that’s ‘1.0.0’. Within this directory, there is a package.yaml file, and then whatever data is associated with the package.

Rez uses the package.yaml to identify foo’s dependencies, which are then added to the configuration in an attempt to resolve it. Foo’s package.yaml may look something like this:

config_version : 0

name : foo

uuid: 80540458-859f-11df-9cc4-002564afe6ee

version : 1.0.0

authors:

- freddy.mac

- fannie.mae

description:

- does foo-type stuff

requires:

- boost-1.37.0

- openexr-1.6.1

commands:

- export PATH=$PATH:!ROOT!/bin

Some entries are self-explanatory, but here are descriptions of the ones that aren’t:

config_version - A version number to retain backwards compatibility, in case the format of package.yaml files changes in future. For the moment this should be set to zero.

uuid - a unique identifier, whos purpose is to stop naming conflicts between packages. In Rez, all packages must have a unique name. You can generate this string using the uuid builtin linux command. This identifier should stay the same for all subsequent releases of the package.

requires - the dependencies of this package. These entries name other packages, and they can (and often are) inexactly versioned.

commands - This is a list of bash commands. If this package becomes part of a resolved configuration, then these commands will be executed in order to create the resolved environment (we’ll get to this process later). A special variable - !ROOT! - is expanded out to the install location of the package at run-time. In this case, it would expand to /rez/packages/foo/1.0.0.

So, this package requires packages boost-1.37.0 and openexr-1.6.1, and if pulled into an environment, it will add it’s ‘bin’ directory to $PATH in order to expose its executable binary, ‘foo’. Appending to $PATH is a typical example of the kinds of commands you will see in package.yamls. Others include:

appending $LD_LIBRARY_PATH, for shared libraries;

appending $HOUDINI_DSO_PATH, for houdini plugins;

appending $CMAKE_MODULE_PATH, to allow other packages to build against us (more on this later).

In order to expose third-party software to the Rez system, the above directory structure needs to be setup, and the package.yaml written. Typically, an ‘ext’ symlink is added which points at the installation, rather than moving the installation into the packages directory. For internal software, the package.yaml and relevant directory structure is created for you, as part of the release process, and the project itself is installed in the same place, as per our ‘foo’ example above.

We’ve just described the anatomy of a simple package, and where to find them. There are more to packages, but we’ll talk about package variants later.

rez-env

All this talk of packages and rez-config is all well and good, but let’s actually do something already. Specifically, let’s use rez-env to create environments on the fly.

For just one moment, let’s go back to rez-config. There’s another flag I didn’t touch on. ‘--print-env’ will print a sequence of bash commands that will, if executed, create the environment containing the resolved configuration you asked for. For example, here’s the output I get when asking for an environment with the latest rv:

> rez-config --print-env rv

export REZ_RESOLVE='rv-3.8.6 lin64'

export REZ_LIN64_ROOT=/rez/software/packages/lin64

export REZ_RESOLVE_MODE=latest

export REZ_RV_VERSION=3.8.6

export REZ_FAILED_ATTEMPTS=0

export PYTHONPATH=/rez/ext/python/lin64/2.5/pyyaml/3.9.0:/rez/ext/python/lin64/2.5/pydot/1.0.2:/rez/ext/python/lin64/2.5/pyparsing/1.5.1

export REZ_RV_ROOT=/rez/packages/rv/3.8.6/lin64

export REZ_LIN64_VERSION=

export CMAKE_MODULE_PATH='/rez/packages/rez/1.40/cmake'';'/rez/packages/lin64/cmake

export PATH=/bin:/usr/bin:/rez/packages/rez/1.40/bin:/rez/packages/rv/3.8.6/lin64/ext/bin

export RV_LICENCE_SERVER=rvlic01.int

export REZ_PLATFORM=lin64

export REZ_REQUEST='rv'

All the environment variables beginning with ‘REZ_’ are Rez system variables, and should not be touched. The environment contains metadata - that is, data describing how this environment was generated, and what the result was (eg REZ_REQUEST, REZ_RESOLVE). All other variables have been created from package.yaml command lists.

rez-env is a tool which uses rez-config in order to start a sub-shell with the environment you requested. Like rez-config, it accepts a list of packages as a request. Here’s what happens when you invoke rez-env:

[~/workspace]$ rez-env rv

You are now in a new environment.

requested packages (mode=latest):

rv

resolved packages:

rv-3.8.6 /rez/packages/rv/3.8.6/lin64

lin64 /rez/packages/lin64

number of failed attempts: 0

context file:

/tmp/.rez-context.FdZyi10798

> [~/workspace]$ _

rez-env resolves the environment, then starts the shell and gives you a printout describing the new environment. Notice the arrow bracket positioned before the prompt (>). This is a visual cue to remind you that you are now within a Rez environment. To get out of the shell simply run the linux builtin command exit. You can run rez-env multiple times, and you will see the nesting by way of multiple arrow brackets (>>, >>> etc). There is no benefit to doing this though - each new shell is independent of the previous one (see the Patching chapter for creating new shells that are based off the current shell).

All information about the current environment is automatically stored into a “context file”. The idea is that this context file can be stored with data to give it context - for example with a maya scene, or sent to the farm - so that that data can be used in the same environment it was created in. When the user exits from an interactive rez-env shell, the context file is deleted.

If you ever need to remind yourself of what shell you are in, you can use the helper utility rez-context-info. It simply shows the same printout you see above - the one you get after invoking rez-env.

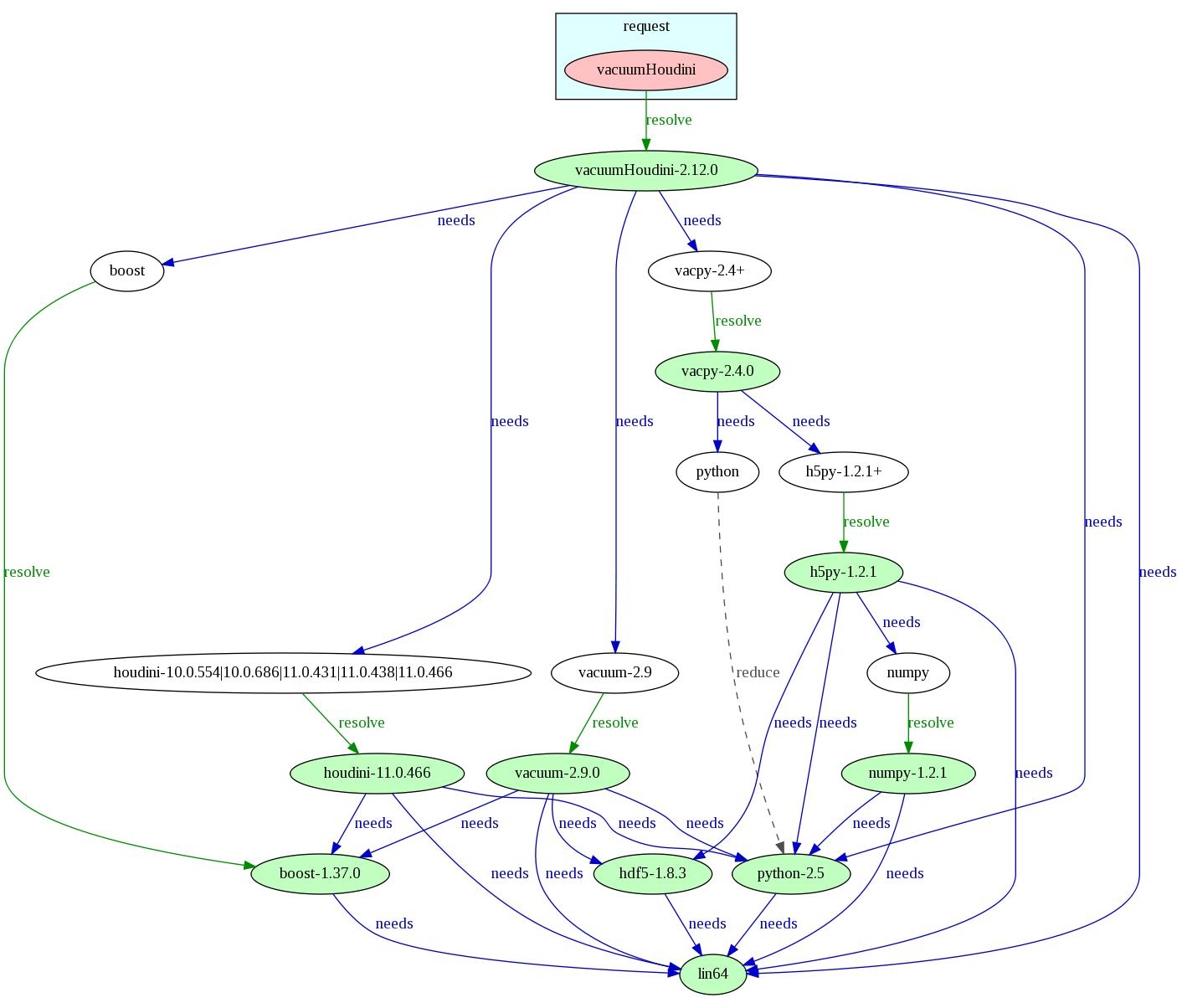

If you are ever curious about exactly how the current environment was resolved - and why exactly did I end up with Qt-4.2.0 rather than Qt-4.5.3? - the rez-context-image tool is very useful. Here is an example, showing how the environment was resolved for “latest vacuumHoudini”:

Nodes in the ‘request’ box are the packages that were requested, and green nodes are the packages that were resolved for the current environment. The arrows show relationships between packages, and there are three different types:

needs - This shows a standard package dependency.

resolve - This shows that rez-config searched for this version of the package on the file system. Look toward the left of this diagram - “boost” is an inexact package request, and in this case rez-config had to search through REZ_PACKAGES_PATH to find a suitable version of boost. This is different to when package requests or requirements are specifically versioned - a ‘resolve’ only occurs if rez-config had to search for a package, within an inexact range.

reduce - This happens when a package is added to the configuration, but either a subset or superset of that package is already in the configuration. This either has no effect, or ‘reduces’ the existing package request to a more specific request. In this example, “python” was in the configuration, and as a result of “h5py-1.2.1” being added, it’s requirement “python-2.5” was then added, which “reduced” the existing “python” package to the more specific, and in this case exact package, “python-2.5”.

These “resolve graphs” can become extremely large. Rez-context-image supports a “--package” flag which can be used to reduce the graph down, so that it only contains packages that are directly or indirectly dependent on the specified package. In the example above, we could have specified “--package=numpy” to see only that part of the graph branching upwards from the numpy package.

Patching

Sometimes you end up in a situation where you want to add some more packages to the current environment, or change the version of some package(s), or even delete a package. This is called patching in Rez. The example illustrates:

[~/workspace]$ rez-env rv hdfview

You are now in a new environment.

requested packages (mode=latest, time=1301976231):

rv

hdfview

resolved packages:

hdfview-2.6.0.1.1 /rez/packages/hdfview/2.6.0.1.1/lin64

lin64 /rez/packages/lin64

rv-3.10.11 /rez/packages/rv/3.10.11/lin64

number of failed attempts: 0

context file:

/tmp/.rez-context.KiIWl30871

> [~/workspace]$ rez-env --add_loose cmake rv-3.10.10

request: rv-3.10.10 hdfview cmake

You are now in a new environment.

requested packages (mode=latest, time=1301976255):

rv-3.10.10

hdfview

cmake

resolved packages:

cmake-2.8.0 /rez/packages/cmake/2.8.0

hdfview-2.6.0.1.1 /rez/packages/hdfview/2.6.0.1.1/lin64

lin64 /rez/packages/lin64

rv-3.10.10 /rez/packages/rv/3.10.10/lin64

number of failed attempts: 0

context file:

/tmp/.rez-context.NFhps31171

>> [~/workspace]$

In this example, we jumped into a shell containing ‘rv’ and ‘hdfview’. Once in that environment, we then patched the environment, adding a new package ‘cmake’, and specifying a particular version of ‘rv’. Note how the version of rv in the second environment changes.

Take note of the prompt after the patch. You will see two arrow brackets (‘>>’). This is because the act of patching has put you into yet another subshell. Why is this? Because it isn’t possible to simply add a package to the current environment, or change a package version. When any change is introduced, the whole environment has to be re-resolved - otherwise, the changes you introduce may cause package version clashes (‘conflicts’). When patching, rez-env uses the packages you give it, plus the current environment variable $REZ_REQUEST (which contains the request list for the current environment), to assemble a new package list.

There are two different kinds of patching - loose and strict. The difference is subtle but important. Loose patching takes your additional packages and applies them to the current request in order to create a new environment. Strict patching applies your changes to the current resolve instead (using $REZ_RESOLVE rather than $REZ_REQUEST). A strict patch has less chance of resolving without conflicts (because there are more packages in the resolve than the request, and they’re all exact version numbers), but it will create a new environment as similar to the current one as possible. A loose patch has a greater chance of resolving, but at the cost of more changes being introduced to the environment. Generally you will tend to use loose patching.

A final note on patching. To delete a package, you use a leading ‘^’ on an unversioned package. For example, to remove ‘hdfview’ from the previous example we would do this:

> [~/workspace]$ rez-env --add_loose ^hdfview

Piping and rez-run

There are many occasions, especially in parts of a pipeline, where you want to run a command in a specific environment non-interactively. For example, there may be a script that gets run somewhere which needs to start another script in a particular production environment - perhaps in order to render a turntable, or publish an asset. For whatever reason, you might not already be in the environment that you need.

You may be tempted to try and solve this problem by doing something like this:

[~/workspace]$ rez-env houdini ; my_hython_script

However, you’d quickly find that this doesn’t work. The reason is because rez-env puts you into an interactive shell - the second part of this command (‘my_hython_script’) won’t run until after you’ve exited that shell.

You can get around this problem using piping. Piping a command into rez-env is done with the -s flag (analogous to bash’s own -s flag). Our previous example, corrected to use piping, would look like so:

[~/workspace]$ echo my_hython_script | rez-env -s houdini

The -s flag effectively means take commands from standard input, rather than from an interactive shell. Don’t make this mistake:

[~/workspace]$ my_hython_script | rez-env -s houdini # WRONG!

This would run ‘my_hython_script’ in the current environment (which probably wouldn’t work), and would then pipe the output into the new rez-env environment, to be run as commands.

Piping can get confusing, especially when we start piping into environments within environments (this particular case happens with wrappers). Variable expansion can also be difficult to get right. Because of this, there is another tool, rez-run, which makes running commands within a given environment easier to do.

Here is an example of using rez-run. The equivalent (and not as nice) command using rez-env and -s is shown first:

[~/workspace]$ echo my_hython_script | rez-env -s houdini

[~/workspace]$ rez-run houdini -- my_hython_script # same as above!

Rez-run also supports a really short form, where the name of the package matches the command to run:

[~/workspace]$ rez-run rv

# same as running “rez-env rv”, then “rv”

Failed Resolves

Recall that rez-config is a recursive algorithm, which searches for a combination of packages that do not contain version clashes. Sometimes, several package configurations are attempted, but are found to fail (ie, they contain version clashes), before the successful combination of packages is found. Recall the example in the previous rez-config chapter, where the request for houdini and boost-1.33.1 causes several such failures before the resolve was successful. So, what happens when no such successful combination exists? Or, what if a large number of failures occur, and you want to find out what’s going on?

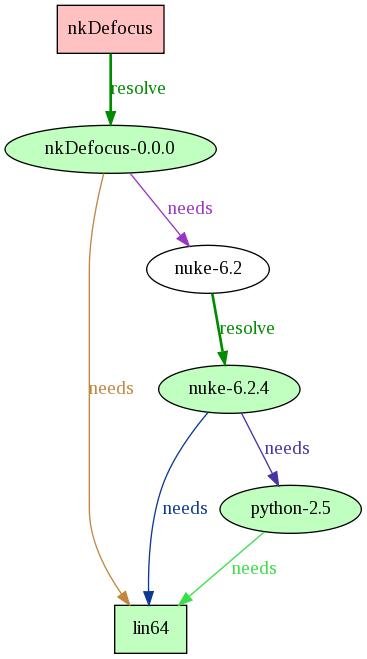

Rez-config is able to create a dot-graph showing the resolution process for a successful resolve, but it can also do this for a failed resolve. Consider the example below, and the graph showing the successful resolve:

]$ rez-env nkDefocus

requested packages (mode=latest, time=1318562365):

lin64

nkDefocus

resolved packages:

lin64 /.../software/packages/lin64

nkDefocus-0.0.0 /.../software/packages/nkDefocus/0.0.0/lin64/nuke-6.2

nuke-6.2.4 /.../software/packages/nuke/6.2.4/lin64

python-2.5 /.../software/packages/python/2.5/lin64

number of failed attempts: 0

From this graph we can see that the “nkDefocus” package indirectly depends on “python-2.5”, via “nuke-6.2”. So what happens when we try another request, this time with a different python version, 2.6:

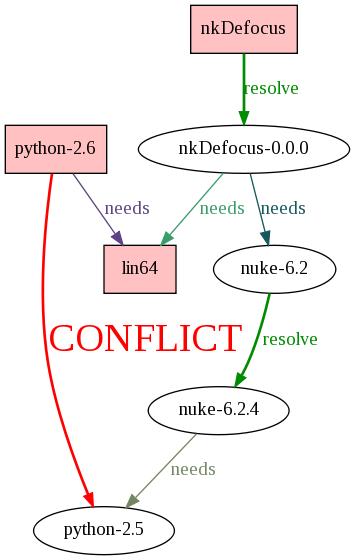

]$ rez-env nkDefocus python-2.6

conflict 0: lin64 nkDefocus-0.0.0 python-2.6 nuke-6.2.4

conflict 1: lin64 nkDefocus-0.0.0 python-2.6 nuke-6.2.3

conflict 2: lin64 nkDefocus-0.0.0 python-2.6 nuke-6.2.2

conflict 3: lin64 nkDefocus-0.0.0 python-2.6 nuke-6.2.1.b.3

conflict 4: lin64 nkDefocus-0.0.0 python-2.6 nuke-6.2.1

The configuration could not be resolved:

('python', '2.6')

('nkDefocus', '')

('lin64', '')

The failed configuration attempts were:

config: (lin64(r) nkDefocus-0.0.0(r) python-2.6(r) nuke-6.2.4(b)): PkgConflictError: ["('python', '2.5') <--!--> ('python', '2.6')"]

config: (lin64(r) nkDefocus-0.0.0(r) python-2.6(r) nuke-6.2.3(b)): PkgConflictError: ["('python', '2.5') <--!--> ('python', '2.6')"]

config: (lin64(r) nkDefocus-0.0.0(r) python-2.6(r) nuke-6.2.2(b)): PkgConflictError: ["('python', '2.5') <--!--> ('python', '2.6')"]

config: (lin64(r) nkDefocus-0.0.0(r) python-2.6(r) nuke-6.2.1.b.3(b)): PkgConflictError: ["('python', '2.5') <--!--> ('python', '2.6')"]

config: (lin64(r) nkDefocus-0.0.0(r) python-2.6(r) nuke-6.2.1(b)): PkgConflictError: ["('python', '2.5') <--!--> ('python', '2.6')"]

Clearly this hasn’t worked. Rez-env has printed a list showing the conflicts that occurred, but it’s difficult to get a clear picture of what happened from reading this text.

At this point, what you need to do is run the same package request through rez-config, using two flags - --max-fails and --dot-file. The max fails flag tells rez-config to stop trying to resolve the request after a certain number of times - --max-fails=0 is the most common use case, and that will stop after the first failed configuration attempt. The dot-file flag tells rez-config to print the resulting graph to a file - several file extensions are supported. You usually want to write to .jpg, which will render the graph to a jpeg file, but you can also write to a native .dot file too. Here then, is the command to run to debug this request, and the graph that results:

$] rez-config --max-fails=0 --dot-file=fail.jpg nkDefocus python-2.6

Here we can see what has happened - python-2.5 is required by nuke-6.2.4, which rez-config resolved (ie found on the file system) from a request for nuke-6.2, which was required by nkDefocus-0.0.0, which was resolved from the request for nkDefocus... which clashes with the request for python-2.6. The conflict is shown as a bold red arrow labelled “CONFLICT” (in case you missed it).

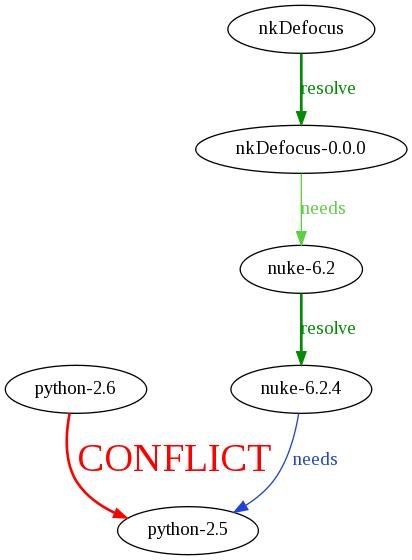

This graph can get extremely big, if lots of packages are involved. It can become hard to even see where the conflict has occurred. In this case, you can pare the graph down to show just those packages that are connected, directly or indirectly, to the conflict. To do this, write to a .dot file rather than a .jpg, and then view this file with the rez-dot utility and the flag --conflict-only. We haven’t seen rez-dot yet - it’s just a small utility for viewing dot files. rez-context-image uses it, and shares all the same flags. Here is the same conflict graph, this time pared down to only those packages involved:

$] rez-config --max-fails=0 --dot-file=fail.dot nkDefocus python-2.6

$] rez-dot --conflict-only fail.dot

Package Variants

Variants are a powerful mechanism in package configuration, and they allow for a flexible development environment. Essentially, a ‘variant’ is a particular flavour of a package, that has one or more dependencies that are different to other variants in the same package.

A good example of package variants in use are houdini plugins. Often, production is using more than one version of houdini at any given time, so logically we want to provide our houdini plugin across all houdini versions in use. Without variants, we would have to maintain separate branches of our plugin for each houdini version - a cumbersome, hard-to-maintain, slow-to-release approach, and one that shouldn’t be necessary if all we need to do for each houdini version is recompile our plugin.

In Rez, the author of such a package would provide variants of their package, one for each version of houdini they wish to support. Their package.yaml might look like this (note: entries we have already covered have been deliberately missed out):

name: fooHouPlugin

version: 1.0.0

variants:

- [ houdini-11.0.430 ]

- [ houdini-11.1.466 ]

requires:

- ilmbase-1.0.2

Each variant entry is a list of dependencies, no different to the packages listed in the ‘requires’ field. Note that the square brackets [] denote a list in the Yaml syntax, much like python. Package dependencies listed in each variant apply only to that variant, and they also become subdirectories in that variant’s install path. For example, our plugin’s installation would look like this:

/rez/packages/fooHouPlugin/1.0.0/

|-- houdini-11.0.430

| `-- (plugin data, libraries etc)

|-- houdini-11.1.466

| `-- (plugin data, libraries etc)

`-- package.yaml

Rez will determine which variant of your package to use, depending on the configuration being resolved. For example, if you were to run the command:

> rez-env fooHouPlugin-1.0.0 houdini-11.0

You would end up loading the houdini-11.0.430 variant of fooHouPlugin-1.0.0.

You may be wondering how to support variants if, say, houdini-11.0.430’s API has changed from houdini-11.1.466. Clearly the same code can’t be compiled for both variants in this case, since the API change might cause fooHouPlugin to fail to compile for one of the variants. The next section (rez-build) explains how to deal with this case.

rez-build

Rez-build is the tool which bridges the gap between run-time environments and the build system. It uses the package.yaml of the project being built, in order to drive a build matrix over the project. One build will take place for each variant in your project, or just the one if there are no variants. Rez-build creates a rez environment for each build, containing all the correct packages, and then runs cmake/make inside this shell.

rez-build’s command-line arguments are grouped into three parts. The first part are arguments to rez-build itself; the second part are arguments to rez-cmake, a thin wrapper for cmake; and the third part are arguments to make itself. Argument parts are separate by a double hyphen (--):

> rez-build [ rez-build args ] [ -- rez-cmake args [ -- make args ] ]

All arguments are optional, but whether or not the arguments to make are supplied, changes the way that rez-build behaves.

Case 1: Not invoking make

Let’s assume that we’re in the same directory as a project we wish to build (we’ll use the previous example, fooHouPlugin). The project’s package.yaml is in the same directory, as is its CMakeLists.txt file, which is a cmake build file. Consider the following command:

> rez-build --

Here, we have supplied no rez-build args, and no rez-cmake args, but we have also specifically missed out the second double hyphen (--). By doing this we are effectively saying, we do not want to actually build the project - we do not want to invoke make. So, what what are we doing then? Here’s rez-build’s output:

---------------------------------------------------------

rez-build: building for variant 'houdini-11.0.430'

---------------------------------------------------------

rez-build: invoking rez-config:

requested packages: ilmbase-1.0.2 houdini-11.0.430

package search paths:/users/xxx/packages:/rez/packages

Generated /users/xxx/fooHouPlugin/build/0/build-env.sh, invoke to run cmake for this project's variant:(houdini-11.0.430)

---------------------------------------------------------

rez-build: building for variant 'houdini-11.1.466'

---------------------------------------------------------

rez-build: invoking rez-config:

requested packages: ilmbase-1.0.2 houdini-11.1.466

package search paths: /users/xxx/packages:/rez/packages

Generated /users/xxx/fooHouPlugin/build/1/build-env.sh, invoke to run cmake for this project's variant:(houdini-11.1.466)

In this case rez-build has created two subdirectories, ./build/0/ and ./build/1/, one for each of the package’s variants. These paths are always numbered 0..N, and the order matches the order of variants found in the package.yaml (ie, ./build/0 in this case refers to the ‘houdini-11.0.430’ variant). Under the build subdirectory, there are also symlinks pointing at the numbered directories, and these links contain the names of the packages in each variant, in case you’re unsure as to which directory matches which variant.

In each of these subdirectories, rez-build has create a script called build-env.sh. If you cd into this directory and execute this script, two things will happen:

- You will be launched into a sub-shell containing all the packages this variant is dependent on;

- cmake will be run automatically, which will generate your Makefile(s).

You will now be in an environment very similar to a rez-env environment. You will notice the arrow bracket visual cue as usual (>), and again you can use the linux builtin command exit to exit this build environment.

Once in this environment, you can make your project as you would for any normal make-based project. As long as your project doesn’t change configuration, you can continue to alter code, compile and recompile. However doing things which change the project configuration will mean you’ll have to exit out and re-run rez-build. Such actions include:

Adding new source files to the project;

Changing the dependencies of the project in the package.yaml;

Changing the variants in the package.yaml;

Changing the build type (eg Debug, Release);

Changing how source files are built - for example changing cflags in a C++ project.

Generally, changes to your package.yaml or CMakeLists.txt will necessitate re-running of rez-build.

Case 2: Invoking make

Let’s say that we don’t have a need to repeatedly alter and rebuild a project, and that we just want to build the whole thing at once, from a single command. We do this by including the make-part of rez-build’s args list:

> rez-build -- --

I won’t include the output here as it will be fairly verbose, needless to say that the above command will build every variant of your project. For each variant, it does the following:

- Launches the appropriate environment, based on that variant’s dependent packages;

- Runs cmake in order to create the relevant Makefiles;

- Runs make, in order to build the variant.

Cmake Arguments

As mentioned, the second set of arguments are passed to rez-cmake, a thin cmake wrapper script. Please note that rez-cmake is currently fairly limited in the control it gives you - you should consider updating it to suit your studio’s needs.

At the time of writing, the common arguments passed here are those that control the type of build. “-t Debug” will perform a debug build, and “-t Release” (the default), a release build.

It could be argued that rez-cmake should be removed completely, and the arguments here be passed directly to cmake, for more control. This is left as an exercise for the user.

Make Arguments

The third set of arguments to rez-build are passed along to make. Since Cmake is actually generating the make files, you should consult its documentation for further information on the make arguments that it makes available. Suffice to say, here are some useful arguments to know:

VERBOSE=1: This will print all the build commands (compiling, linking etc) to standard out.

install: We’ve already described this common make argument, which will, for us, locally install our package, typically to $HOME/packages/

-jN: Utilises N threads to speed up the build process.

Local Package Installs

Ok, so far so good. I can build a project and all its different variants with a single command, and I don’t have to worry about setting up the correct build environment, because rez-build does this for me. But what if I want to test my project? Recall the REZ_PACKAGES_PATH environment variable, whos typical value looks like this:

${HOME}/packages:/some-configured-location/packages

That first directory is you local packages directory, and it’s the same for everyone (note that the actual location is configurable and determined when rez is installed). When you want to test packages that you are developing before you release them, this is where you install them to. This location is configured when rez is initially installed.

To locally install your package, just invoke rez-build, but tell make that you want to do an install:

> rez-build -- -- install

Hey presto! Your package will now be installed to your local packages directory. To test it, just rez-env as per usual. Since your local packages directory is at the start of rez-config’s search paths, rez-env will pick your local package up before the same central package. Here’s what might happen in our case, given that we have just locally installed fooHouPlugin and wish to test it:

> rez-env fooHouPlugin

You are now in a new environment.

running rez-config v1.40

requested packages (mode=latest):

h5_test

resolved packages:

ilmbase-1.0.2 /rez/packages/ilmbase/1.0.2

fooHouPlugin-1.0.0 /users/joe.bloggs/packages/fooHouPlugin/1.0.0/houdini-11.1.466 (local)

houdini-11.1.466 /rez/packages/houdini/11.1.466

number of failed attempts: 0

context file:

/tmp/.rez-context.hNSPkc6560

> [~/workspace]$ _

Notice that the rez-env info printout shows that fooHouPlugin is now being picked up locally. At this point, I’ll assume that fooHouPlugin’s package.yaml file is adding the plugin to the houdini plugin path (via ‘commands’ in the package.yaml, as was mentioned earlier). So to test, we would probably load up houdini, and then test the plugin.

If you are working on several projects locally, and they have interdependencies with one another, rez-build will pick up local packages when building variants, just as rez-env does when creating a shell. If you want to cease using a local version of a particular package, you can simply delete the package from your local packages directory. Alternatively, if you want to cease picking up local versions of any package at all, you could remove your local packages directory from REZ_PACKAGES_PATH manually.

Cmake Integration

In order for rez-build to drive your project’s build matrix from the package.yaml, your CMake build file must use some cmake functions, and include some cmake modules, which are released as part of rez-config. Please note that a full description of cmake and its language is beyond the scope of this document - to find out more on how to use cmake, take a look at - http://www.cmake.org/cmake/help/cmake-2-8-docs.html

Here’s an example of what fooHouPlugin’s CMakeLists.txt might look like:

CMAKE_MINIMUM_REQUIRED(VERSION 2.8)

include(RezBuild)

set(boost_USE_STATIC_LIBS ON)

set(boost_COMPONENTS program_options)

rez_find_packages(PREFIX pkgs AUTO)

include_directories(include)

add_definitions( -DBOOST_VER=${BOOST_VERSION} -DBOOST_MAJ_VER=${BOOST_MAJOR_VERSION} )

add_houdini_plugin( SOP_FooDeformer src/Foo_Deformer.cpp )

target_link_libraries( SOP_FooDeformer ${pkgs_LIBRARIES} )

INSTALL ( TARGETS SOP_FooDeformer DESTINATION dso)

I’m going to go into detail about those sections shown in bold. Everything else in this file is native cmake code, which I won’t go into detail about.

include(RezBuild)

The top-most cmake build file (that is, the CMakeLists.txt in the same directory as package.yaml) must include this line before anything else (excluding the cmake mandatory CMAKE_MINIMUM_REQUIRED statement). This file takes information from environment variables that rez-build has setup, and exposes them within cmake. It also calls the cmake standard function project(), passing it the name of the project as it was specified in the package.yaml. (Note: do NOT call project() directly yourself, this will break the build).

set(boost_USE_STATIC_LIBS ON)

set(boost_COMPONENTS program_options)

Here is an example of some variables being set, which control aspects of a package which we are building against. Specifically, we are specifying that we want to statically link against boost, and that we want to use the boost program_options library.

Every package can have different input variables, or even none at all. What these variables are, and what they do, is dictated by the package itself. Many packages are installed with their own cmake module, which is typically installed under a ‘cmake’ subdirectory, with the file name

A package providing its own cmake module will expose this module to cmake by adding the path to $CMAKE_MODULE_PATH, via a command in its package.yaml. If you are using a package which provides its own cmake module, you should refer to the module itself for any documentation describing

what variables are available to set.

Please note that setting input variables such as these MUST happen before calling the next function, ‘rez_find_packages’.

rez_find_packages(PREFIX pkgs AUTO)

This function does a lot of work, and it’s the reason rez-build-enabled CMakeLists.txt files are often shorter and more succinct than normal CMakeLists.txt files.

To begin explaining what it does, I first have to point out some optional arguments that are missing:

rez_find_packages(package1 package2 packageN PREFIX pkgs AUTO)

‘rez_find_packages’ iterates over a list of packages, and if a list is not supplied, it iterates over all packages in the current build variant. For each package, it does the following:

- It includes that package’s cmake module, if there is one (ie, the package’s

.cmake file, found somewhere in $CMAKE_MODULE_PATH); - If a cmake file was found, they are combined into four output variables - $PREFIX_INCLUDE_DIRS, $PREFIX_LIBRARY_DIRS, $PREFIX_LIBRARIES and $PREFIX_DEFINITIONS. These variables represent the compile flags and link flags that we need in order to build a C++ project against these packages. In the current example, the output variables would be ‘pkgs_INCLUDE_DIRS’ etc.

After the packages have been iterated over, and if AUTO is set, then the function also automatically sets up include directories, library directories and C++ definitions for your project.

You’ve probably noticed that this section seems pretty C++-centric, and you’d be right. However, in theory there is no reason why a non-C++ package could not provide its own cmake module, providing its own information and control over how to use the package. ‘rez_find_packages’ would still attempt to create the C++ output variables that have just been mentioned, but it doesn’t matter if these variables are empty, and it would still load the cmake modules for each package.

A more in-depth discussion of rez_find_packages is beyond the scope of this document. For the best available documentation on this and other Rez cmake functions, see the in-source documentation in the cmake modules themselves (in the rez installation under cmake/), and look at the example packages that ship with rez, found in examples/demo/projects.

add_definitions( -DBOOST_VER=${BOOST_VERSION} -DBOOST_MAJ_VER=${BOOST_MAJOR_VERSION} )

This line of code will pass some definitions to the C++ compiler, in this case the version of boost, and just the major boost version. It illustrates the fact that rez-build automatically exposes package dependency version information to you via cmake variables. In this example, the boost-related variables that have been created are:

BOOST_VERSION (eg: 1.37.0)

BOOST_MAJOR_VERSION (eg: 1)

BOOST_MINOR_VERSION (eg: 37)

BOOST_PATCH_VERSION (eg: 0)

These variables are created for every package that the current variant depends on. If packages have less than three version number components, the extra values will be set to zero. This functionality becomes important when supporting variants that may have a differing API. By passing version information through to your compiler’s preprocessor, you can write #ifdefs to change your code, depending on which variant is being built.

target_link_libraries( SOP_FooDeformer ${pkgs_LIBRARIES} )

‘target_link_libraries’ is a native cmake command, but this line of code is worth a mention because it illustrates use of one of rez_find_packages’ output variables, in this case pkgs_LIBRARIES.

CMake Modules

Rez supplies several cmake modules, one of which we’ve already covered (rez_find_packages). Following is a list of other available modules. For more documentation, see the comments in the source files themselves (as mentioned - /rez/packages/rez/${VERSION}/cmake).

rez_install_cmake

Builds and installs a cmake module for your project. This is the cmake file that the rez_find_packages macro will find, when compiling and linking other packages against yours. You typically use this when building a C++ library which other libraries or binaries will link against. See the translate_lib example project in the rez install for an example of this.

rez_install_files

Installs data files. There are native cmake functions which can do this (specifically, the install command in modes DIRECTORY and FILES), but they both have issues - DIRECTORY copies a directory wholesale, and requires exclusion patterns to skip svn metadata etc, and FILES loses subdirectory structure on installation. rez_install_files suffers neither of these problems. You can also install files and set executable permissions on them with the EXECUTABLE keyword.

rez_install_python

Installs python source files. Once upon a time this macro used to build the associated pyc files and install them also, however python’s management (or lack thereof) of bytecode meant that this feature had to be removed. Regardless, this macro will check to see that a ‘python’ package appears in the current package list, and will fail if this is not the case. This macro should probably be updated so that pyc files are compiled for the purposes of checking for errors, but not installed. This is left as an exercise for the reader.

Build-time Dependencies

Sometimes it is desirable for a package to depend on another package only for the purposes of building its code, or perhaps generating documentation. Let’s use documentation as an example - a C++ project may need to builds its docs using doxygen, but once the docs are generated, doxygen is no longer needed.

This is achieved by listing build-time dependencies under a build_requires section in the package.yaml, instead of the usual requires section. For example:

name: foo

version: 1.0.0

requires:

- ilmbase-1.0.2

build_requires:

- doxygen-4.5

rez-build invokes rez-config with the -b flag at build-time, which tells rez-config to include the build requirements in the resolve, as well as its usual requirements. Note that a package’s build requirements and normal requirements can overlap, but not conflict - for example, it would be acceptable to require foo-1.5 at build-time, and foo-1 at run-time.

Another typical use of build requirements is for static libraries. If two separate libraries or applications A and B, link statically to two different versions of the same third library C, then this will often not cause a problem at runtime... A and B can safely be used within the same resolved environment. Rez allows this case - in both A and B’s package.yaml files, you would list the C package as a build-only requirement.

Building Custom Targets

You will probably find yourself needing to build source code or assets not natively supported by Rez. Examples include - shader source files; Houdini OTL files, and so on.

Recall that many packages provide their own cmake source file, named

commands:

- export CMAKE_MODULE_PATH=$CMAKE_MODULE_PATH:!ROOT!/cmake

The Rez cmake macro rez_find_packages will find this cmake file, and automatically include it. So, providing new cmake macros for building new kinds of targets is just a case of creating a package which provides all the relevant cmake source to do this, in its cmake file2. These kinds of packages usually just provide this cmake source, and nothing else, and the convention we’ve followed at Dr D Studios has been to name these packages buildTools_XXX. For example, our package which provides the cmake source for building and installing Houdini OTLs is called buildTools_houdini. Packages that need to build OTLs, include this package as a build-time requirement, and then simply use the cmake macros made available.

Please refer to the example build tools package in the rez distribution (“buildTools_toupper”) for more information. Note that the cmake file contains a block comment at the top, listing the available macro, usage information and a description of all the arguments. You should do the same in your own build tool cmake files.

Timestamping

When a package is built and installed with rez-build, it has a timestamp associated with it. All of the rez tools which resolve environments - rez-config, rez-build, and rez-release (which we’ve yet to cover) allow the user to “roll back time”, by setting the “current” timestamp to a time in the past. When this is done, rez ignores packages with a newer timestamp than the “current” timestamp. Using this feature, you can replicate a resolve that would have happened in the past.

Let’s see an example. Say you use rez-config to list the resolved packages for some package “foo”:

$] rez-config --print-packages foo

foo-1.0.0

bah-5.6.1

eek-5.4.4

Let’s assume that the current date is October 20, 2.50pm, 2011. Rez denotes timestamps using the epoch time format, ie the number of seconds that have expired since 1970. Let’s say that the 5.4.4 patch to “eek” occurred yesterday, at October 19, 1.30pm, 2011. The epoch time can be calculated like so (on linux) using the standard date utility:

$] date --date=”Oct 19 13:30 2011”

1318991400

So let’s now do another resolve, but this time, rolling time back to October 18th, the day before eek was patched:

$] date --date=”Oct 18 13:30 2011”

1318905000

$] rez-config --time=1318905000 -print-packages foo

foo-1.0.0

bah-5.6.1

eek-5.4.3

As you can see, the version of “eek” that has been resolved is now different, because “eek-5.4.4” did not exist at that point in time.

The timestamp feature is useful in cases where you want to rebuild an old piece of software, but you want to know how its environment resolved back when it was installed. Perhaps, for example, you’re having problems rebuilding the project, because of new package versions that are now getting pulled into the build environment (in theory this shouldn’t be a problem, if people version their package updates appropriately, but theory isn’t practice!). Using timestamping you can go back to the original build time, and then move forward until you identify the problem. Another thing you can do is simply compare the packages that were resolved at the old built time, with the packages that are resolving now, using the rez-diff tool (see the More Tools chapter for a description).

Timestamping is also important because it is used by rez-build every time you build a package. If you have a package with multiple variants, those variants are built one after the other (they can’t be built all at the same time). If a new package was released during the build process, one variant might get the new package version, and another might not, even though they’re both requesting the same thing. To avoid this inconsistency, rez-build takes note of the time before it starts building any variants, and then forces all variant environment resolutions onto this timestamp, thus making sure that they all see the same existing packages, and not any very new ones.

Anti-Packages and the Conflict Operator

When using rez-config and supporting tools, you generally speak in terms of what you want - eg “rez-env houdini rv”. However, it is sometimes necessary to speak in terms of what you don’t want, and rez-config lets you do this too.

Consider two fictitious packages foo and bah. Let’s say that both foo and bah cannot exist in the same environment at the same time, because they conflict with each other in some way that cannot be understood by Rez - ie, they do not have conflicting dependencies, but conflict nonetheless (there could be a multitude of reasons for this, that we won’t get into here). We want to say that “bah requires NOT foo”. We would do this like so, in this case from bah’s package.yaml:

requires:

- ‘!foo’3

Now, any attempt to create an environment containing both foo and bah will fail. We could, if we wanted to, state the vice-versa in foo’s package.yaml also, although this is unnecessary. The exclamation mark operator here is analogous to its use in many programming languages, ie it means NOT. You can use the exclamation (or ‘conflict’) operator with any valid package description, exact or inexact.

A package request combined with an anti-package request will cause a conflict only if the package request falls entirely inside the anti-package version range - otherwise, the result is the difference of the two. To put this in less confusing terms, consider these examples:

| Package | Anti-Package | Resolved Package |

|---|---|---|

| foo-3.2 | !foo | conflict |

| foo-3.5 | !foo-3 | conflict |

| foo-7 | !foo-3 | foo-7 |

| foo-4+ | !foo-5+ | foo-4 |

| foo | !foo-3 | foo-0+<3 |

Weak Package References

A weak package reference is a way of saying “I do not need this package, but if it exists then it MUST lie within the version range I specify.” Consider this example for the theoretical package bah:

requires:

- ~foo-5

In this example bah does not require foo, but if foo is part of a package resolution involving bah, then it must be within the version range ‘5’.

Weak package references are just a shorthand way of saying “I require NOT the inverse of this package,” and within the Rez system this is actually how they are represented. So for example:

~foo-5

is equivalent to the anti-package:

!foo-0+<5|6+

Note that the system does actually convert a weak package reference into the equivalent anti-package as soon as it sees it, and if it appears in a dot-graph then it will appear as this anti-package, rather than the weak package reference. A weak package reference, therefore, is just a shorthand notation used to create a conflict package.

rez-release

So now you know how to use rez-config to query the system for information; you know how to use rez-env to create run-time environments; and you know how to build, locally install and test packages in development. Now you probably want to be able to ‘release’ a package - that is, install it centrally so that production, and other developers, have access to it. ‘Rez-release’ is the tool which does this.

Rez-release must be run from the same directory as your package.yaml file. All of rez-release’s arguments are optional, please see ‘rez-release -h’ for more information. To release a project, you must be in a working svn directory, and you must be in the correct location. For a project ‘foo’, you must be in either of these svn urls:

/.../.../foo/trunk

/.../.../foo/branches/<branchname>

When rez-release is run, the following actions occur:

The svn state of your project is checked. If there are modified files, or if the project is out-of-date, then rez-release will abort. Your project must be up-to-date in order to be released.

The version of your project is checked (this in in your package.yaml). If this version is <= the currently-installed version, rez-release will abort. If this happens, you need to update your version, svn-checkin, and then rez-release once more (A note on version numbers - PLEASE follow the conventions outlined in the ‘Conventions’ chapter).

For each variant, a clean copy of the project is checked out of svn into a clean subdirectory, and is built locally.

If all variants build successfully, then each is installed centrally. When this happens, rez-release also installs a set of metadata files into a hidden directory called .metadata (you can find this in the same directory as the installed package.yaml file). The directory contains - the changelog for this release; a dump of the actual environment that the variant was built in; the svn location the release was tagged in; and the time when the release occurred.

You are then presented with a release log, which you can add comments to. The log is loaded into an editor which is controlled by the environment variable REZ_RELEASE_EDITOR. If you close this editor without making any changes, rez-release will prompt you with a request to ‘(a)bort or (c)ontinue’ the release. This is normal behaviour and is not an error - much like command-line svn, the system is just giving you a chance to stop the release. To continue, type ‘c’ and

. The svn ‘trunk’ of your project is then tagged under the new version number. This tag will appear at /.../.../foo/tags/

.

It must be noted that, for those emergency situations, rez-release will allow you to release to a version that is earlier than the latest release. You can do this by specifying the flag --allow-not-latest. This should only be used when absolutely necessary. Rez-release will never let you release to an already-released version.

The Release Process

A typical release process for a project would follow this checklist:

- Update the project version. This is found in the package.yaml file. What kind of version update is done (major/minor/patch/other) depends on the changes you have made (see the chapter “Conventions - Versioning (Internal Software)” for more details).

- Check your changes into svn.

- Ensure your project is up-to-date with the svn repository (eg ‘svn update’);

- Run ‘rez-release’ from the terminal, in the same directory that contains package.yaml.

After successfully running rez-release, your package will have been released into the location specified by the environment variable $REZ_RELEASE_PACKAGES_PATH - this is the ‘central’ package location. This variable is automatically setup for you by rez. Recall the $REZ_PACKAGES_PATH variable, the one that rez uses to search for packages:

${HOME}/packages:/some-configured-location/packages

REZ_RELEASE_PACKAGES_PATH will typically be the second entry, shown here in bold.

Packages of Packages - Bundles and Wrappers

So far we’ve talked a lot about packages, and how Rez resolves a package request in order to create a working environment. But is this enough to build an environment management system on top of? Let’s play devil’s advocate for a moment now, and point out two issues.

Firstly, do we really want many users to keep having to re-resolve the same list of packages for, say, a particular show, or shot, or application, over and over again, every time they jump into that environment? There’s a few problems with this:

This will probably cause quite a lot of file stats, as many users query many packages, probably over a network, and often in order to resolve the same environment, which seems wasteful.

The environment can change at any time between requests. For example, if the request asks for “foo-1.2”, and a new foo patch is released, then one user might get that patch and another might not - it depends on when each user resolved a new environment. This may or may not be desirable.

What if the resolve fails? It’s probably not a good idea to expose many users to a problem like this, that is technical in nature, and that they shouldn’t really be having to worry about. An animator, for example, is not going to know how to fix a package resolution failure, and probably shouldn’t need to know either.

Secondly - often working in a shot involves using several different applications. So, we probably need a way of grouping packages into separate lists, one for each application. For example, if you’re using Maya, why should you need to resolve a bunch of Houdini plugin packages? We need to have a way of grouping packages together, and somehow exposing them to the user. We might want to have a “Maya” package group, and a “Nuke” package group, or maybe a “Comp” package group that contains the Nuke package, as well as a few other compositing-specific packages. We may even want to have quite specific groupings - for example, a “maya-anim” package group for maya animators, and a “maya-fx” package group for vfx maya users.

Another reason for grouping package requests, is that the smaller the package request, the less chance of version conflicts, and the less your software is forced to be released in lock-step with other software. For example, if you have a single environment containing Maya and Houdini, and plugin packages for both that use the boost C++ library suite, then you will be forced to provide maya and houdini plugins that share a common boost version. If, however, you keep your Maya and Houdini package groups separate, then you don’t have this limitation (let’s forget that Rez variants make this problem pretty easy to deal with though!).

Two new kinds of package in this section help to deal with these issues, wrapper packages being perhaps the most significant.

Bundles

A bundle is just the name given to a package which does nothing but require a list of other packages. For example, an “rnd” package might collect a set of core technology packages into a single bundle. The “rnd” package’s package.yaml file might look like this:

name: rnd

version: 5

description: Core technologies bundle.

requires:

- fooAssetManager-1.4

- logging-5.4

- farmManager-8.0

Even though bundles don’t actually build anything, they still need a CMakeLists.txt file like every package. However, all you need to put into a bundle’s CMakeLists.txt is the following:

CMAKE_MINIMUM_REQUIRED(VERSION 2.8)

include(RezBuild)

Bundles succeed in grouping packages together, but that’s about it (sometimes though, that’s all you want). If you requested two different bundles, you’d still end up with a single environment, containing all the packages from both bundles, and all their dependencies. Note however, that bundles give you the ability to succinctly start an application in its own shell, like so:

$] rez-run anim_maya_bundle-1 -- maya

Wrappers

A wrapper is a package that creates a package resolve, and a set of scripts which act as entry points into the resolved environment. Think of wrappers as pre-resolved, ‘baked’ environments, that have been configured for a group of packages ahead of time.

When you resolve a package list with, say, rez-env, a “context” file is created, which contains all of the data needed to create the resultant environment. A wrapper package actually uses rez-config itself to build a context file, and then installs that context file for later use. Wrappers are probably best explained with an example, so here we go.

Let’s say we want to create a group of packages for Maya animators. We might want that group to contain Maya, and a set of animation plugins. Following is our “maya_anim” wrapper package’s package.yaml file, and CMakeLists.txt file (note that irrelevant details have been left out):

#------------------------------------

# package.yaml

#------------------------------------

name: maya_anim

version: 1

commands:

- export PATH=$PATH:!ROOT!

- export REZ_WRAPPER_PATH=$REZ_WRAPPER_PATH:!ROOT!

#------------------------------------

# CMakeLists.txt

#------------------------------------

rez_install_wrappers(

maya_anim_wrapper

maya_anim.context

maya_anim

PACKAGES

maya-2009

bendyLimbs-5.6

poser-4.3

WRAPPERS

animmaya:maya

DESTINATION .

)

The first thing you’ll notice is that there’s almost nothing in the package.yaml, and in particular, there are no dependent packages listed at all. All the action is in the CMakeLists.txt

The CMakeLists.txt defines a single wrapper using the rez_install_wrappers macro (note that it is possible to create several wrappers in a single package, if you want). This wrapper is given a cmake target name of maya_anim_wrapper (the first argument); it will create and install a context file called maya_anim.context (the second argument); the wrapper will be called maya_anim (the third argument - more on this later). It contains the packages maya-2009, bendyLimbs-5.6 and poser-4.3; and it creates a script called animmaya.

When this package is built, it will call rez-config and create a resolved environment for the request “maya-2009 bendyLimbs-5.6 poser-4.3”. It will then install this as a context file. It will also create the “animmaya” script.

To use this wrapper, you just request it as you would any package. The “animmaya” script is an executable bash script, and will be added to PATH (because of the command in the wrapper’s package.yaml):

> rez-run maya_anim -- animmaya

When you execute “animmaya”, the command “maya” is executed inside the pre-resolved environment. No package resolution takes place (apart from the trivial resolution of the single wrapper package), because this already happened when the wrapper package was built and installed. The environment that maya runs in cannot change either, again because the resolve has happened ahead of time. This is quite different to running the command:

> rez-run maya-2009 bendyLimbs-5.6 poser-4.3 -- maya

...which is a normal resolve - the resolution takes place when the command is run, and the resolve might be different when run a day later, or even ten minutes later (for example, there maybe be a newly patched bendyLimbs package released by then).

We can use several wrapper packages within the same environment. This lets us present a shell to the user that seems to have many different tools available in one environment, but in reality these tools execute inside their own insulated “wrapper” environments. The figure below illustrates:

IMG

Here we have an environment that contains two wrappers, one for Maya animators (“maya_anim”) and another for Houdini vfx artists (“houdini_vfx”). While it looks to the user like a single environment which contains the tools “animmaya”, “vfxhoudini” and “vfxhython”, in reality these tools run inside their own pre-baked environments, insulated from packages in other wrappers.

The wrapper scripts rez creates (“animmaya” etc) can do more than just execute the tool they wrap. Consider the case where you might want to test a new Houdini vfx plugin version in the existing “houdini_vfx” wrapper (say, “shatter-1.1”). To do this, we’d have to be able to somehow get into the environment inside that wrapper so that we can patch it (patching is already explained in an earlier chapter). You can do that by using the flag ---i:

$] rez-env maya_anim houdini_vfx

$] >

$] > vfxhoudini ---i

$] > houdini_vfx>

$] > houdini_vfx> echo $REZ_RESOLVE

houdini-12.0.10 shatter-1.0.0 explode-0.4.1 fxUtils-2.1.0

We’ve now jumped inside of the “houdini_vfx” wrapper environment! This is signified by the ‘houdini_vfx >’ prompt. “houdini_vfx” is shown because this is the name of the wrapper that we are inside of. If you used the ---i flag on either “vfxhoudini” or “vfxhython”, you’d end up inside the same wrapper, and so you’d have the same label added to the prompt. Now that we’re inside the wrapper environment, to test the new “shatter” plugin version, you just do a patch as normal:

$] > houdini_vfx> rez-env --patch_loose shatter-1.1

You are now in a new environment.

[the rest removed for conciseness]

Rez-run also works with wrapper packages!

$] rez-run houdini_vfx -- vfxhython -- echo ‘$REZ_RESOLVE’

houdini-12.0.10 shatter-1.0.0 explode-0.4.1 fxUtils-2.1.0

You can even get a bit freaky. Here’s a single command which will print the resolve list of a wrapper that we’ve patched on-the-fly (rez-run supports the same patching flags that rez-env does):

$] rez-run houdini_vfx -- vfxhython -- “rez-run --patch_strict shatter-1.1 -- echo ‘$REZ_RESOLVE’”

houdini-12.0.10 shatter-1.1.0 explode-0.4.1 fxUtils-2.1.0

There’s one last important point to cover on wrappers. What if you need to invoke a wrapper script from within another wrapper? For example, a Maya user might be in a Maya session, which is inside the “maya_anim” wrapper. They then need to start Nuke from within Maya, to run some kind of automated compositing subprocess. This kind of thing happens all the time. But what we’d like is to be able to use a particular Nuke wrapper from within Maya, since it’ll be configured with our compositing plugins.

This works already. By default, if you create an environment which is a collection of wrappers (eg “rez-env maya_anim houdini_vfx”), all the wrappers become visible to one another. Recall the package.yaml file for our wrapper example:

name: maya_anim

version: 1

commands:

- export PATH=$PATH:!ROOT!

- export REZ_WRAPPER_PATH=$REZ_WRAPPER_PATH:!ROOT!

Without going into details, that last line in bold appends a special environment variable called REZ_WRAPPER_PATH. Rez-config uses this path to ensure that wrappers are visible to one another. In order for this to work, you must append to this value, as shown above.

You can jump into wrappers within wrappers within wrappers too, there is no limit (it would be rather odd to want to do this though):

$] rez-env maya_anim houdini_vfx

$] > animmaya ---i

$] > maya_anim> vfxhoudini ---i

$] > maya_anim> houdini_vfx> animmaya ---i

$] > maya_anim> houdini_vfx> maya_anim> fun..?

Exposing Third-Party Software to Rez

So, rez-release is the tool used to centrally install packages that are developed internally. But what about third-party software and applications? They need to be exposed to Rez in the same way - that is, they need to have the correct directories present in the packages path, they need to supply a package.yaml, and they may need to supply a cmake module of their own.

The short answer is that this is done by hand. In future, it would be nice to support a rez package file format, and a utility that will take these files and convert them into rez packages on disk.

Packages for third-party software follow a certain convention. The installation itself does not have to be moved into the packages directory - instead, it is pointed at via an ‘ext’ symlink. Command entries in the package.yaml then reference this ‘ext’ link when setting paths etc for the package. Please follow this convention if integrating your own third-party software with Rez.

If the third-party package is a C++ library then it will need to provide a cmake file which follows the conventions outlined in the Rez-build chapter. This allows rez-build to determine the necessary cflags and ldflags in order to compile and link other packages with the library. In an internal package (ie one built with rez-build), this cmake file is typically generated by using the rez_install_cmake macro.

More Tools

There are a number of extra Rez tools that we haven’t described yet.

rez-make-yaml

When starting a new project, you’re going to need a new package.yaml, and this tool will generate one in the same directory it was called from. You’ll still need to edit it afterwards, but it does most of the ground work.

rez-info

Prints information about the given package.

rez-diff

This tool will list the differences between two versions of a package, or two sets of packages. It lists the changelog entries for each package, and can write this info out in html format.

rez-help

Displays help for a package, if help is available. The following examples show how to add help entries to your package.yaml file. Note that you can use the special expanding variable !ROOT! in help entries as well - you will need to do this when referencing documents that have been installed as part of the package.

# this package has one help entry

help: firefox http://www.foopkg.com/manual

# this package has multiple help entries

help:

- [ “user guide”, ‘firefox http://www.foopkg.com/manual’ ]

- [ “reference manual”, ‘kpdf !ROOT!/docs/refman.pdf’ ]

rez-which

This tool prints the path to the most recent package which falls within the version range you ask for. For example, ‘rez-which rv-3’ might print ‘/rez/packages/rv/3.10.11’. Note that rez-which is in no way affected by the current environment.